Treaties of 1817 and 1819

On July 08, 1817, the Treaty of Cherokee Agency was signed in present-day Calhoun, Tennessee by three-hundred Cherokee heads-of-households to become American citizens (McLoughlin 3). Each signatory was to be awarded 640 acres of land and the allotments were located in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama (McLoughlin 3). The signing of this treaty benefited the men two-fold, they acquired land and were thus granted citizenship because they held land outside of the “bounds of the Cherokee nation”(3). This treaty was part of a larger U.S. political project of acculturation of mixed-race Cherokee of European ancestry (4). This treaty was also a part of a “civilization policy” constructed by Secretary of War, Henry Knox whose aims were to: “. . . extinguish all tribal titles to land, denationalize the tribes, and leave only individual Indian landholders scattered as farmer-citizens among the whites (a program which would place millions of acres of uncultivated Indian land on the market for sale to expand white settlements in the West) (4). The Treaty of Cherokee Agency was a programmatic tool of coercion to give up Cherokee lands and thus their political and economic power (4). The Cherokee were also threatened with forced removal and relocation to the west of the Mississippi river if they did not “denationalize” by selling their incorporated land (4). The Cherokee nation retaliated against citizens who sold their land or emigrated by rescinding their citizenship (5). Cherokee leadership eventually came to a compromise by selling 3.8 million acres of land to the U.S to maintain communal ownership 10 million acres of ancestral land through the Treaty of Washington (1819) to preemptively fight against forced relocation (5).

Euchella v. Welsh (1824)

This case affirmed landholding and citizenship rights of the Cherokee in North Carolina. Plaintiffs included Euchella and fifty-nine other heads-of-households who settled along the Little Tennessee, Tuckasegee, and Ocanaluftee rivers to gain their 640 acres granted in the Treaties of 1817 and 1819. They became aggrieved at the realization that white settlers were infiltrating the land granted to them. North Carolina had sold some of the land to white settlers. The state admitted fault and compensated the Cherokee by granting them land elsewhere (Godbold 5). Euchella moved back to tribal lands while others plaintiffs, most notably, Yonaguska sold their land plots and moved once again (Godbold 5). Yonaguska settled on the convergence of Soco Creek and Oconaluftee River(5). The Cherokee who moved back to tribal lands like Euchella were citizens of North Carolina and thus, the United States (5). People like Yonaguska, who were alongside the other aggrieved Cherokee who all became formally known as the Eastern Band and established the Cherokee Reserve within the Qualla Boundary. Members of the Eastern Band were thus, not citizens of North Carolina and the United States.

Early Cherokee Government Political Organization and the Constitution of the Cherokee Nation (1827) New Echota, Georgia

From the early eighteenth century, the tribal council controlled political affairs of the town and between towns. Councils were arbiters of the law and served as mediators of dispute. They handled cases between individuals and clan disputes within its jurisdiction. The council was comprised of the entire populace but was led by three bodies:

1. Town priest chief

2. Seven elders advisory council (elders from seven clans of Cherokee nation and served as an inner advisory to chief)

3. Beloved men (other prominent senior men of a given town)(Perisco 93)

The move toward a more centralized power was a response and remedy to the hyper-localization of politics as the town was the only legitimate political unit. The unification of all towns of the Cherokee nation, formed the Cherokee national council: “the Cherokees found it necessary to alter their political organization in response to white pressure to create a system that the whites could understand”where a centralized tribal government was used to oversee relations, particularly in terms of commerce with non-natives and was precipitated out of the need to politically and economically legitimize (Perisco 94). The nation was divided into eight districts and New Echota, Georgia was deemed the nation’s capital and John Ross was appointed as the head of the new national government and held its highest office (Blackmun 244).

By 1825, a set of articles were adopted by the Cherokee national council to gain more control over lands of the Cherokee nation. The implications of the Cherokee having more autonomy of the land empowered the tribal government to not only control its land, but the power to conceptualize and grant citizenship to the people that lived within its borders. This was a direct affront to the United States’ move to forcibly remove the Cherokee to gain the nation’s land and its resources. With citizenship, came specific rights and protections that would be outlined in the constitution of Cherokee nation in 1827.

Preamble, Constitution of the Cherokee Nation, 1827

“We, the Representatives of the people of the Cherokee Nation, in Convention assembled, in order to establish justice, ensure tranquility, promote our common welfare, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of liberty; acknowledging with humility and gratitude the goodness of the sovereign Ruler of the Universe,in offering us an opportunity so favorable to the design, and imploring His aid and direction in its accomplishment, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the Government of the Cherokee Nation.“

The Preamble is a testament of how similar in language and ideals (specifically republicanism and inalienable rights endowed by a creator) the Cherokee Constitution was to the United States Constitution and illustrates not only the influence, but the dedication to securing political and legal legitimacy in the eyes of the U.S federal government. The Constitution also served as a means to articulate sovereignty, self-determination, and a collective Cherokee political consciousness. The Cherokee’s politically discursive nature centered land rights and land use:

- Article 1 & 2- Stated that all lands and annuities were public property

- Article II: The general council exclusively held the right to dispose of public property

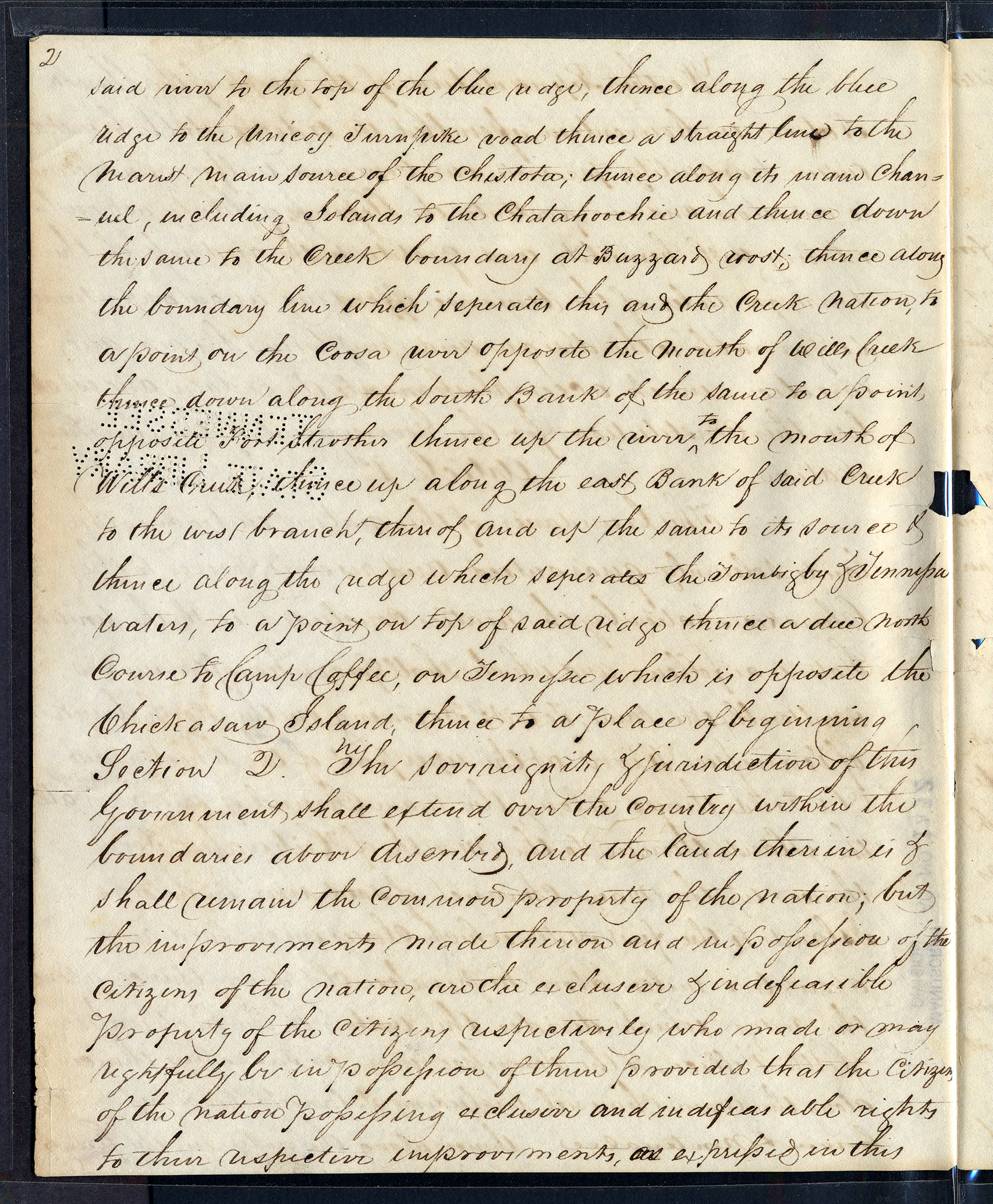

Article 1, Sec. 1. :

The boundaries of this Nation, embracing the lands

solemnly guaranteed and reserved forever to the Cherokee

Nation the treaties concluded with the United States, are as

follows, and shall forever hereafter remain unalterably the

same, to wit . . . [extended, detailed descriptions of national

boundaries].

Article 1, Sec. 2. :

The Sovereignty and Jurisdiction of this Government shall extend over the country within the boundaries above described, and the lands therein are, and shall remain, the common property of the nation.

The Cherokee Nation followed a governance tradition in linking nationhood and territory within a legal and geopolitical framework and its role in establishing jurisdiction, “Consequently, ‘failure to observe the emerging tribal laws came to be considered as treason in the context of the fight for tribal lands’ (Brown 47). This historical moment in the conceptualization of the Cherokee Constitution is particularly important in the questions of sovereignty in the face of white settler colonialism while the codification of law surrounding land cemented Cherokee opposition to white U.S. legal hegemony.

The same year the Constitution was adopted, the Blue Ridge Turnpike was completed (Blackmun 262). While the population of counties east of the Blue Ridge mountains decreased, populations west of them increased as well as the encroachment of Cherokee land (Blackmun 262).

Read about some key figures and political leaders in Cherokee history.