Tsali (?-1838)

Tsali, or Charley was a Cherokee elder who resided along the Natahala river during the forced Cherokee removal of 1838 and to evade removal, hid in the mountains of Western North Carolina where thousands of others had sought refuge (Finger 1). The same year Second Lieutenant Andrew Jackson Smith, of the First Dragoons got wind of Indian “fugitives” nearby and embarked on their capture. In collaboration with other native “fugitives”(including Euchella) and the Oconaluftee (including William Holland Thomas), the U.S. army captured Tsali and his family. Native collaboration in the capturing of other Natives further complicates the narrative that there was an “us against them” mentality between Whites and Natives. The Ocanaluftee and the Cherokee (tribal members of the Cherokee nation) fighting against removal for themselves illustrate the guileful nature of the federal government and its ability to coerce people to do its bidding by forcing their hand while people’s literal lives were at stake, ” [William Holland] Thomas determined that those Cherokee retaining tribal status and trying to avoid removal should not jeopardize the right of the Oconaluftee band to remain; consequently, both he and his Indian wards sometimes assisted the army in its roundup of tribal members”(Finger 5). Tsali, along with his three eldest sons killed one soldier and injured two others as they were detained. Major Winfield Scott ordered the execution of Tsali and his sons. Tsali surrendered and negotiated with the U.S. to cease further removal and relocation of North Carolina native Americans, leveraging his life for the lives of the rest. Tsali is considered a hero and a martyr that resisted removal and brutality at the hands of the U.S. military.

Yonaguska Drowning Bear (1759–1839)

1st Principal Chief of the Eastern Band Cherokee as he was the sole Chief of North Carolina that refused removal and retreated into the mountains, but was not up to task to lead his people after federal troops retreated (Blackmun 242). He appointed his adoptive son, William Holland Thomas as new chief in hopes that he would be able to remedy the affects of the “white man[‘s] greed” (Blackmun 242).

William Holland Thomas (1805-1893)

William H. Thomas

Thomas was white but adopted by Chief Yonaguska, making him a member of the Eastern Band Cherokee. He was a local businessman and became the Band’s legal counsel in 1831 and served as a liaison to the U.S. federal government during and after Cherokee removal (Adams 134). He played an integral part in the capture of Tsali but also ensured that the Ocanaluftee of western North Carolina remained in North Carolina as his work as a federal agent. He eventually became the second principal chief following the death of his adoptive father, “The first step taken before he became chief was to go to Washington in behalf of his people, pleading for aid for them and asking for their share of the $5,000,000 that the federal government had agreed under treaty to pay the Cherokees for their eastern land . . . ” (Blackmun 258). Thomas purchased land in his name with Cherokee funds , received a legal title for the land and called it the Qualla Boundary (Adams 135). New geographical restrictions emerged however, ” The 1874 court decision placed a new geographical restriction on tribal citizenship:ownership of the common territory was limited to ‘the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians living in the State of North Carolina, as a tribe or community, and whether living at this time at Qualla or elsewhere in the State” (Adams 135).

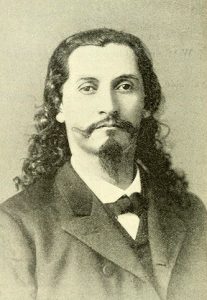

Nimrod Jarrett Smith (1837-1893)

Nimrod Jarrett Smith

Smith was the fourth principal chief of the Eastern Band who was a dynamic leader who came up with an innovative solution to white encroachment on tribal lands, he incorporated the lands under the state laws of North Carolina: “Incorporation helped protect the Band against trespassers by validating the Eastern Cherokees’ tribal organization and communal ownership of the tribal lands” (Adams 136). With incorporation, the Band could have standing in court as well as pursue lawsuits as a collective as well as control the entirety of the Qualla boundary (Adams 136). The encroachment of new white settlers setting claim to land within the Qualla boundary and their declaration of Cherokee heritage illustrates the paradoxical nature of white privilege and race and the incorporation of the Qualla boundary,”This dual recognition (by the state as a corporation and by the federal government as a tribe) produced a confused legal situation. Were the Cherokees citizens of North Carolina or of the United States, or were they “wards”under direct control of the federal governments?” (Mitchell 144). White people had the ability to move across racial and citizenship lines whenever they thought it proved beneficial to them, whereas Native Americans largely where disadvantaged socially and economically because of race and tribal status. With forced relocation in the living memory of many, including Chief Smith, I can’t help but think there was some level of resentment against the whites claiming to be Cherokee. Once the federal government recognized the Eastern Band as an official tribe, the Interior Department was granted supervision of Eastern Band affairs. Illustrating the freedom and constraints of being recognized as an official tribe, the tribe had legal protections in official courts of law, but also had to seek approval for many of its decisions (including the sale of the resources produced by the land) (Adams 138). The tribal council thus, found it necessary to create new citizenship criteria over the concerns of tribal resources (Adams 139). Post-incorporation, the tribe went into business deals with lumber companies and distributed funds to each tribal citizen, cementing the economic desirability of becoming a tribal citizen of the Eastern Band (Adams 139). The Band decided that they needed an official roll to document legitimate citizens of the Eastern Band Cherokee nation and informed their decisions regarding citizenship based on blood-quantum, enrollees had to be at least 1/16 Cherokee to qualify.

James E. Henderson

Was the North Carolina federal superintendent of the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs. He encouraged many EBCI members to register for the draft and serve in World War I, although Eastern Band members were considered non-citizen wards of the U. S. (Finger 284). Congress had passed a bill requiring all citizens and non-citizens males from the ages of 21 to 30 to register with local boards to sign up for service in 1917 (Finger 286).

David Owl

The nephew of the Principal Chief Sampson Owl ( 1923-1927), penned a letter to Superintendent Henderson regarding the legality of requiring non-citizens or wards to register for the draft (Finger 286). Henderson said he didn’t understand the legality regarding conscription but provided insight into why the Cherokee should volunteer to register anyway, “There is a certain element among the Cherokees who like to be citizens when it is to their best interest to be so and wards of the government when it is to their best interest” (Finger 290). The following year, David was drafted and deployed to France to fight in the war, while he was still considered a noncitizen along with nearly 90 other Eastern Band Cherokee (Finger 291).

Image Credits: