Blood Quantum

Blood quantum is a socio-legal concept that emerged out of rudimentary American race science wherein people understood that blood defined lineage and ancestry. Ancestry and lineage had to be clearly defined for people of color so that they could be easily defined and identified within the legal system. The concept of blood quantum underpins the more colloquial term coined “Indian blood”, an individual could not claim to be a member of a tribe if their quantum was measured to be low. A person was required to prove that they met the blood quantum threshold (1/16th) to be considered a tribal member (Adams 140).

Dawes Roll

List of members of the “Five Civilized Tribes” (Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Seminoles, and Chickasaw) who proved their ancestry, and thus citizenship to these nations who were then entitled to land allotments from the U. S. federal government from the years 1898-1914. This roll is still used to this day to determine tribal membership.

Jus Sanguinis

Literally translates to “right of blood” is when a person acquires citizenship through their parents or ancestors citizenship of a given state. This legal concept is completely at odds with the mechanisms put in place to define Indian tribal membership through blood quantum, disqualifying any member and their offspring from citizenship eligibility.

Jus Soli

Literally translates to “right of the soil”, but refers to birthright citizenship, a major place of contention for Native American tribes and their strife with the U.S government . This legal concept rules that any person born within a jurisdiction’s soil is considered a citizen of that place. Birthright citizenship was denied to native Americans who maintained tribal membership of an Indian nation, even though they were born in the United States.

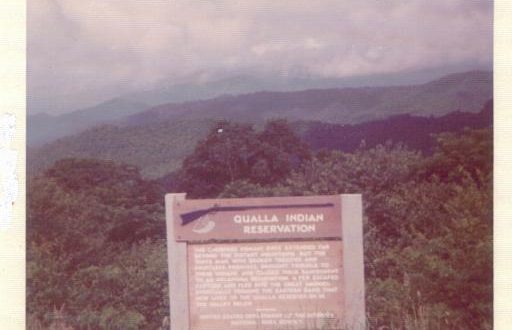

The Ocanaluftee

The native Americans of Western North Carolina who renounced Cherokee citizenship following the Euchella v. Welch ruling and settled along the Oconaluftee river, hence the name.

Timber Fund

The tribal council first sold their timber rights of the Cathcart Tract for $15,000 in the 1890s and then sold the Love Tract for $245,000 in 1906 (Adams 139). Tribal citizens were promised monetary payouts through per-capital payments by the council through this fund, thus calling into question of the nation who was entitled to money coming from these land sells.

White Indians

White people who feigned Cherokee ancestry to have access and acquire tribal land. The proliferation of white Indians in Cherokee country speaks to the economic advantages whites wished to gain. Thus, creating a more nuanced narrative surrounding privilege and economic mobility in terms of race in western North Carolina and other native nations.